This week in Manhattan, Ground Zero isn’t the only repository of grief and longing. At the Marriott Marquis Theater in midtown, you’ll find a different kind of mourning going on. Before the curtain rises on the current revival of Follies, Stephen Sondheim’s 1971 elegiac musical, the audience is treated to a scene familiar to that which has been unfolding at the island’s tip for the last 10 years. Construction site drop clothes envelop the theater’s interior like a shroud; these bilious clouds of gray transform what, to my mind, is one of Broadway’s least desirable houses into a setting that would make the ghosts of those who trod the boards back in the days of Ziegfeld proud. Such a setting (in line with its plot, a last hurrah for those performers who played it the night before it’s to be torn down) is a wounding reminder of one of the most ignoble events in New York theater history. Lest we forget, the Marquis is its own Ground Zero—the Morosco, the old Helen Hayes, and the Bijou theaters were demolished to make way for the hotel that now occupies the site. Also, the show’s reappearance eerily mirrors itself and the city’s still-tender tragedy: the last time Follies was revived was the spring of 2001, mere months before the crash came that shook the world, and changed New York forever.

Follies is a love letter to time and memory, those states of mind for who progress, and more time, alas, fails to keep the wrecking ball at bay. The characters who populate this show are haunted by ghosts: their youthful selves take the stage (seen in the present and the past, the doubling of actors creates a macabre funhouse effect) alongside the showgirls who, once upon a time, were the living embodiment of a certain type of musical theater exemplified by helmers like Ziegfeld and Busby Berkeley. Costumed by Gregg Barnes in grand constructions of sequins and drapery these women—spectrally stalking the stage and rafters of Derek McLane’s haunting set—communicate the death of this era heartbreakingly without ever uttering a word.

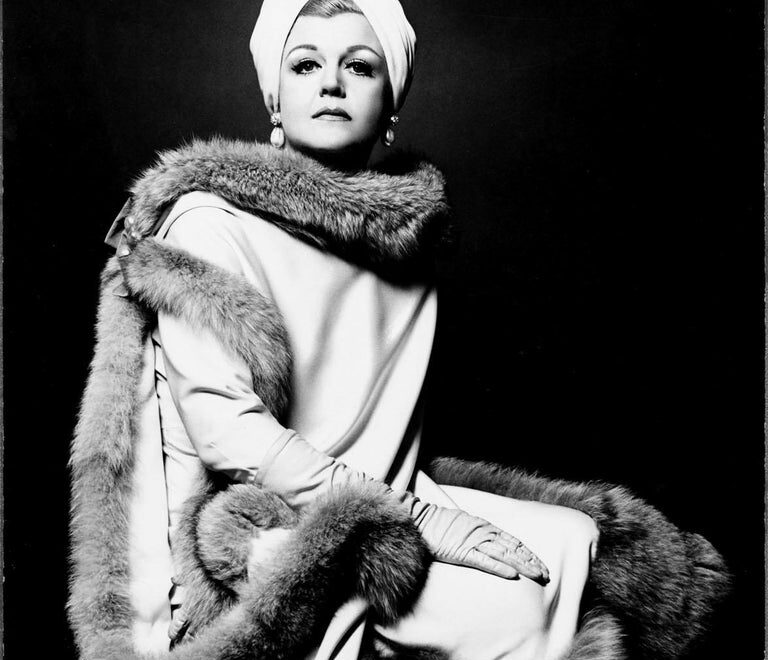

The bearish Ron Raines as Benjamin Stone is just that, a monument of a man whose edifice slowly crumbles. As Buddy, Danny Burstein provides a galvanizing synthesis of pain filtered through a physical dynamic that is electric; this is a watershed for Burstein, an actor who keeps peaking with every new role (for Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, all is forgiven). The role of Phyllis Rogers Stone is a plum (Alexis Smith created it, and won a Tony; Blythe Danner was nominated for the 2001 revival), and Jan Maxwell is a wry, hectoring presence throughout, whether dancing up a storm in “The Story of Lucy and Jesse” (a homage to Kurt Weill’s “The Saga of Jenny” from Lady in the Dark) or spewing disillusionment in Sondheim’s masterful “Could I Leave You?” She’s almost matched by Bernadette Peters as Sally Durant Plummer, who sings the show’s best songs (“In Buddy’s Eyes” and “Losing My Mind”) with all the pathos she can mine from them. But hers is the most difficult role: is Sally crazy, or, like all the other characters, going through her own version of a mid-life crisis? I felt Peters took the manifestations of her fragility too far, to the extent that Ben’s current attraction seemed ridiculous. Maybe it’s something to do with the orchestra’s tempos (especially in Sally and Ben’s duet “Don’t Look at Me”). The night I saw it they felt a hair slow, a problem for listeners who’ve spent too many hours playing the original 1971 cast recording.

My bad—seems like the ghosts will get you every time. This Follies is still a miracle, a haunting peek into the way we once were, and will never be again. It’s an inescapable metaphor for our current New York, which is cause enough for us to welcome it back. When art imitates life with such stunning resonance, who are we to mourn?