Published Attitude: The Dancer’s Magazine Fall 2009

Published Attitude: The Dancer’s Magazine Fall 2009

“I think we’re all pretty interesting, and that all of you are pretty interesting.”

Michael Bennett

Young Mickey DiFiglia’s spirit permeates Every Little Step, the captivating, can’t-look-away documentary directed by James Stern and Adam Del Deo; at one point a black-and-white still reveals this teenager in mid-leap under a Manhattan street sign oozing joy, confidence and the kind of ambition that screams, “look out world, here I come.” Those obsessed with theater history minutia know that the Buffalo-born DiFiglia grew up to be Michael Bennett, the seriously gifted choreographer/director whose talent infused such shows as Company, Follies, Dreamgirls and his masterwork, A Chorus Line.

If A Chorus Line is, as one fresh-faced aspirant gushes, “about the history of the dancer in theater,” then Every Little Step, a chronicle about the musical’s 2006 Broadway re-mounting, will become, I suspect, this generation’s The Red Shoes: a gritty, no-nonsense look at a way of life some call madness, others hail as devotion to a beloved art form. Indeed Bennett (seen and heard throughout) isn’t the only ghost haunting the edges of this exploration of the life and times of the modern show dancer. In the film’s opening, as the camera pans a blocks-long line of auditioners waiting in the winter cold, it’s hard not to think about the myriad incarnations of the Broadway gypsy, from those Ziegfeld Follies-era chorines touting only the talent of their pretty faces and long legs, to the Mickey DiFiglias of today, young college/conservatory-trained dynamos who dance, sing and act with scary proficiency.

The backstage story is an enduring trope of 20th century cinema; Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz trod a similar territory, as did Richard Attenborough’s infamous 1989 adaptation of A Chorus Line. One’s thoughts drift to 42nd Street, whose initial scenes presage our current economic reality: right outside the stage door lurks the Great Depression with its bread lines and bankers diving out of what then passed for skyscrapers. Step tells similar tales of sacrifice and frustration as sweeps us up in its no-nonsense gaze. American Idol this isn’t: that glib TV series is an insult to the talent on desperate display. What a bracing corrective to Idol’s notion of dues-free celebrity and talent manufactured by hours spent mimicking tunes off an iPod.

The details fascinate, from the associate casting director Megan Larche (she confides that over 3000 people auditioned for the revival) informing hopefuls that their first audition will consist solely of two pirouettes, to scenes where auditioners wait to hear whether they’re in or out. The waiting: while casters deliberate, performers inhabit this awful, albeit necessary limbo. Out in the hall is where the competition gets sized up (listen, and laugh, as Nikki Snelson obsesses over another candidate (Jessica Lee Goldwyn) who’s perfect for Val, the role Snelson covets), where even the subtle torture of listening to another performer sing can discourage (when they’re good) or galvanize (when they can’t hit the notes). Casting took place over an 8-month period, a fact that pushes contenders to the brink. One of the film’s unexpected fillips occurs when dancer Rachelle Rak confronts casting director Jay Binder over whether or not she’ll play Sheila, the cynical, been-around-the-block gypsy whose story jumpstarts the musical’s coup de teatre, “At the Ballet.” It’s hard not to sympathize—only a scene before she endures a final callback where Binder tells her to recreate the reading she did six months before.

There’s enough material here to serve the immediate story (the casting of the revival) and a far greater one: the making of A Chorus Line, the Pulitzer, Tony Award-winning phenomenon whose initial run lasted 15 years. Many of the musical’s original creators weigh in: composer Marvin Hamlisch reiterates the brilliance of Bennett, as does one of the show’s stars, Donna McKechnie; director Bob Avian, the Tony-Award winning original co-choreographer, knows that one of the challenges is to avoid duplicating the original cast; Baayork Lee (the original’s Connie) re-staged this version, and here, she literally dances the whole show, whether coaching the opening number (the choreography for this sequence with its intricacies of kicks, lunges and turns is a daunting barrage of kinetic movement that still astounds) or taking the final contenders for Cassie though the nuances of The Music and the Mirror.

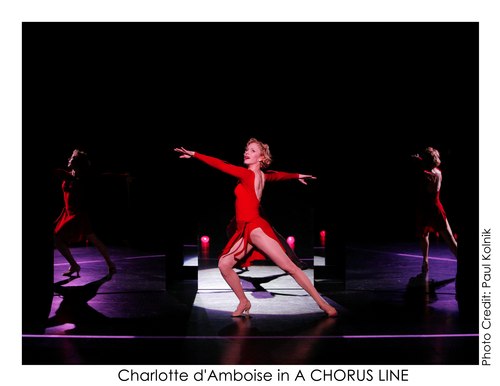

As the auditors keep track of the contenders, the masterful editing by Brad Fuller and Fernando Villena employs quick cuts that allow us to see dancers one in back of the other. We see a revolving door of Mikes, Pauls, Sheilas, Cassies and Maggies (the last, a thrilling montage as singer after singer attempts the final vocal crescendo of “At the Ballet” until red-haired Mara Davi nails the notes, and the role). It’s a trick we never tire of because it allows us to see director Avian’s difficulty, especially when it comes to down to who’ll play the show’s Cassie, the star dancer who “doesn’t dance like everybody else.” In the show she’s failed in Hollywood, and now comes begging for a spot on the line. The film offers quick glimpses of candidates (among them you can spot Meredith Patterson (42nd Street), Amy Spanger (Kiss Me Kate and the current Rock of Ages) and Elizabeth Parkinson, a former member of the Joffrey Ballet and the star of Twyla Tharp’s Movin Out) before narrowing it down to Charlotte D’Ambroise and Natascia Diaz. Type-wise, one immediately gravitates towards D’Ambroise, whose physiognomy resembles McKechnie’s—Diaz, shorter, with womanly hips, seems an also-ran until the film captures her quicksilver prowess during one of her callbacks.

If you saw the revival you know who triumphed in the end. If not, Every Little Step will hold you in its grip until its finale, one that plays out on the bare stage of the Broadhurst Theater. They’re all winners, but you’ll leave the movie with bittersweet feelings about the outcome. Having witnessed a near year in the life of these thoroughbreds, you’ll mourn, and marvel at how special creatures put themselves on the line again and again to do what they did for love. They do Mickey DiFiglia proud—long may they reign.